- By Elliott Haut and Brandyn Lau on behalf of the Johns Hopkins Venous Thromboembolism Collaborative

You pack a healthy lunch for your child, but the carrot sticks and apple come home untouched.

You donate to disaster relief, but the supplies sit unused in a shipping container.

You mail a birthday gift to a friend, only to learn that someone stole it from the front porch.

Sometimes you do everything in your power to do the right thing, and yet things fall apart at the last step.

It's a challenge that we've encountered in our efforts to prevent blood clots — or venous thromboembolism (VTE) – at Johns Hopkins. Initially, we focused on ensuring that every patient was screened for their risk of developing VTE, and that they were then prescribed prophylaxis appropriate to their individual risk level. It was no simple task. But over more than 10 years, our systematic approach has helped increase risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis prescribing success to nearly 100 percent.

Yet, as we watched our hospital's prescribing steadily improve, we made an alarming discovery: More than 40 percent of patients missed at least one dose of VTE prophylaxis medication, most commonly due to patient refusal. Overall, 12 percent of all doses were not administered in the hospital; on some floors the missed-dose rate was roughly double that. Heparin was, by far, the most commonly missed medication, we found in a later study.

Our hospital is not unique. Studies in other academic and community hospitals had similar findings.

A missed dose here and there might not sound like a big deal, but the evidence shows that the risk of developing VTE rises significantly after just two missed doses.

These findings drove home the importance of improving every link in the chain of survival, addressing not only prescriber orders but also the final step — when a nurse administers the treatment to a patient who accepts the medicine.

We needed to understand why patients weren't getting their doses, and then find ways to counter those reasons. One, we discovered, was the disconnect between what nurses believed about blood clot prevention and what the evidence tells us.

A big unsubstantiated myth was that when patients are walking around, they no longer need to receive anticoagulant medications or mechanical prophylaxis. This may make sense on the surface — blood pooling in the legs of bedridden people provides conditions favorable for clot formation, so walking theoretically could help prevent that. However, there's no evidence that walking negates the need for VTE prophylaxis. If there were, how exactly would we convert walking activity to a dose of heparin? How many steps substitute for a 5,000-unit heparin injection? How often must the patient walk? What is the "dose"? What is the frequency? Nobody knows.

Nurses aren't the only ones to have heard the "ambulation myth." Many physicians believe it as well.

We needed to counter this and other common knowledge gaps — for example, about the length of time that patients need to wear mechanical prophylaxis or about alternate injection sites if the abdominal area is unsuitable due to a stoma.

We also had to get patients on board by helping them recognize the dangers of blood clots. Although clots kill more people than breast cancer, motor vehicle crashes and AIDS combined, many patients are unaware of the risks. A patient who wouldn't consider refusing antibiotics may quickly decline heparin shots in their belly.

Like most quality improvement projects, this wasn't a one-size fits all approach. Here's how we tackled it over several years:

-

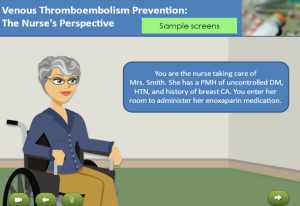

Click on the image to sample the nurse education module on blood clot prevention. Nurse education. Through a brief (20-30 minute) and interactive educational module, we helped nurses understand the evidence behind VTE prevention, dispelled some of the misunderstandings and provided guidance for speaking with patients about the importance of taking all prescribed doses. That module is now available on the Armstrong Institute's online course catalog for a small fee. Johns Hopkins employees can take it via the myLearning platform. You can also sample the module in just a few minutes.

- Patient education. With funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, we created an education bundle — a paper handout and a video — explaining the dangers of blood clots, risk factors and treatments. The video, which can be played on a tablet, smartphone or on televisions in patients' rooms, was made more poignant by the stories of VTE survivors.

- Real-time intervention. In a pilot project on four adult nursing units — two medical, two surgical — we rapidly responded to missed doses with just-in-time patient education. Every time a nurse documented a missed a dose, an alert would be sent via beeper to a nurse educator on the VTE Collaborative team. That nurse, toting the handout and an iPad loaded with the video, would go to the patient room and educate patients and their families about VTE.

While it didn't completely eliminate missed doses, this last intervention reduced them significantly — from 9.1 percent to 5.6 percent of patients, in large part because patient refusal rates dropped. In a control group of units where patients received no intervention, there was no improvement.

We've since spread this real-time intervention strategy to eight clinical units, with nurse leaders from each unit providing the education. Further expansion is planned for the rest of our hospital and then our health system and beyond.

There are times that patients, having been fully educated about the dangers of blood clots, will still refuse prophylaxis, and we always respect their informed decision. However, it's our moral obligation to make sure that every refusal is a conscious decision made by a patient with all the data, statistics and materials needed to make an educated choice. Doing the first few steps right might make us look better on quality measures, but it won't help patients unless they ultimately get the treatments that could save their lives.

Learn more about VTE prevention measures as part of a new Patient Safety Specialization offered by Johns Hopkins Medicine on the Coursera platform. Blood clot prevention is highlighted in the fifth part of the specialization, called Implementing a Patient Safety or Quality Improvement Project.

Elliott Haut, M.D., Ph.D. and Brandyn Lau, M.P.H. are members of the Johns Hopkins VTE Collaborative, a transdisciplinary group that has taken a systematic approach to preventing blood clots and advancing measurement in the field. Dr. Haut is an associate professor of surgery and a core faculty member at the Armstrong Institute. Lau is an assistant professor of Radiology and Radiological Science and associate faculty in the Armstrong Institute.

With declining length of stay, should we be prescribing a short course of DVT prophylaxis to ambulatory discharged patients to reduce VTE?

William-

Great point. There is robust data and much agreement on inpatient approaches to VTE prevention. However, the approach to outpatient (also termed "extended") prophylaxis is more varied. While there is strong data on the benefits in certain populations (i.e. orthopedic joint replacement, abdominal-pelvic cancer surgery), there is sparse data in others (i.e. medical, trauma surgery). Your idea would be great to study, especially since we dont have enough studies to make recommendations.

A missed dose on Mar 23 2005 almost cost me my life during surgery that day. Therefore in Mar 2013 for hernia surgery and Sept 2014 for knee replacement surgery - I had to fight for that infusion before and after surgeries to avoid hemorrhaging.

I had a great time reading your article and found it to be extremely helpful.

Are there any articles or can you share any insights that help to explain why immobility is a significant risk factor for VTE, but frequent/robust safe mobilization is not considered an effective strategy to reduce the risk of developing a VTE in the inpatient setting as compared to pharmacologic prophylaxis?

Trustworthy in our home, trustworthy team members. Dependable service discovered. Dependable excellence.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

One of the best reads I’ve had this week. Enjoy ary tv live — schedules and replays. mobile and desktop friendly. program guide, clips, key moments. mobile and desktop friendly.

This article is worth learning and has been collected. Google Media

**mind vault**

Mind Vault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

**gl pro**

gl pro is a natural dietary supplement designed to promote balanced blood sugar levels and curb sugar cravings.

**sugarmute**

sugarmute is a science-guided nutritional supplement created to help maintain balanced blood sugar while supporting steady energy and mental clarity.

**vitta burn**

vitta burn is a liquid dietary supplement formulated to support healthy weight reduction by increasing metabolic rate, reducing hunger, and promoting fat loss.

**synaptigen**

synaptigen is a next-generation brain support supplement that blends natural nootropics, adaptogens

**glucore**

glucore is a nutritional supplement that is given to patients daily to assist in maintaining healthy blood sugar and metabolic rates.

**prodentim**

prodentim an advanced probiotic formulation designed to support exceptional oral hygiene while fortifying teeth and gums.

**nitric boost**

nitric boost is a dietary formula crafted to enhance vitality and promote overall well-being.

**wildgut**

wildgutis a precision-crafted nutritional blend designed to nurture your dog’s digestive tract.

**sleeplean**

sleeplean is a US-trusted, naturally focused nighttime support formula that helps your body burn fat while you rest.

**mitolyn**

mitolyn a nature-inspired supplement crafted to elevate metabolic activity and support sustainable weight management.

**zencortex**

zencortex contains only the natural ingredients that are effective in supporting incredible hearing naturally.

**breathe**

breathe is a plant-powered tincture crafted to promote lung performance and enhance your breathing quality.

**prostadine**

prostadine is a next-generation prostate support formula designed to help maintain, restore, and enhance optimal male prostate performance.

**pinealxt**

pinealxt is a revolutionary supplement that promotes proper pineal gland function and energy levels to support healthy body function.

**energeia**

energeia is the first and only recipe that targets the root cause of stubborn belly fat and Deadly visceral fat.

**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

**boostaro**

boostaro is a specially crafted dietary supplement for men who want to elevate their overall health and vitality.

**potentstream**

potentstream is engineered to promote prostate well-being by counteracting the residue that can build up from hard-water minerals within the urinary tract.

**hepato burn**

hepato burn is a premium nutritional formula designed to enhance liver function, boost metabolism, and support natural fat breakdown.

**hepato burn**

hepato burn is a potent, plant-based formula created to promote optimal liver performance and naturally stimulate fat-burning mechanisms.

**flowforce max**

flowforce max delivers a forward-thinking, plant-focused way to support prostate health—while also helping maintain everyday energy, libido, and overall vitality.

**neurogenica**

neurogenica is a dietary supplement formulated to support nerve health and ease discomfort associated with neuropathy.

**cellufend**

cellufend is a natural supplement developed to support balanced blood sugar levels through a blend of botanical extracts and essential nutrients.

**revitag**

revitag is a daily skin-support formula created to promote a healthy complexion and visibly diminish the appearance of skin tags.