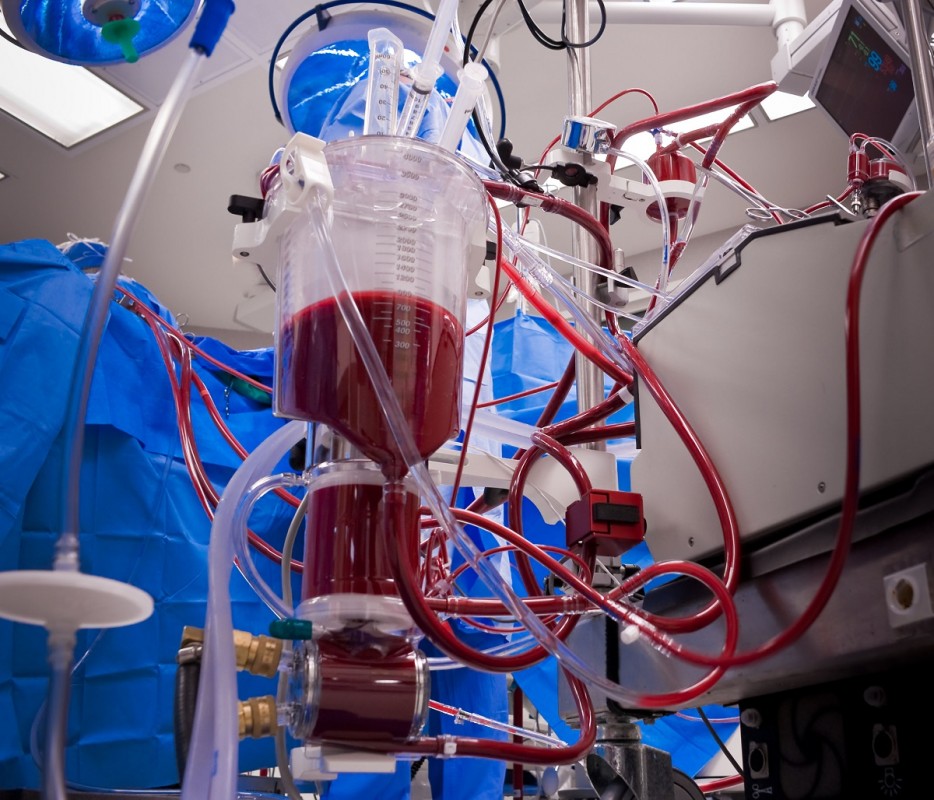

Tens of thousands of people owe their lives to extracorporeal life support (ECLS) — a treatment that uses mechanical devices to perform the work of the heart and lungs for days, weeks or even months when those organs cannot function on their own.

With ECLS, we can give newborns with major congenital defects a fighting chance to live. We can save some patients with sepsis whose organs are shutting down. When CPR fails to resuscitate, even after an hour or more of chest compressions, some patients can be brought back.

ECLS, a set of techniques of which the most frequently used is extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), was pioneered in the 1970s, yet we have seen a huge increase in its use in the last decade. No longer is it a treatment delivered only at large medical centers. Over the last 15 years, the number of pediatric cases using ECLS has doubled and adult cases have at least quadrupled, as have the number of hospitals offering it internationally. A few years ago at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, we had less than 40 ECLS cases per year. This year, we are on track for more than 120.

Technology is one of the factors powering this worldwide growth. In the past, clinical engineers had to build the ECLS circuits with different tubes and devices to take blood from a large vein, oxygenate it and pump it back into the body. But around 2009, off-the-shelf circuits began to appear on the market with more powerful oxygenators and fewer complications.

ECLS’ clinical success is another factor. During the 2009 swine flu pandemic, for example, ECLS roughly halved the death rates of patients experiencing respiratory failure due to the disease, according to one JAMA study.

Among neonatal patients, the survival rate is 75 to 80 percent. For patients supported on ECLS after CPR fails, between 32 and 42 percent survive.

Lack of Standards and Measures

As the use of ECLS grows, it has done so in a somewhat uncontrolled fashion. It's almost impossible to find two centers that use the same clinical policies and protocols for managing these patients. Each hospital has its own protocols, covering such topics as anticoagulation management, blood management, which circuits are used for different types of clinical cases and the criteria for when a circuit needs to be changed.

A University of Michigan study last year has found that survival rates can vary dramatically among ECLS centers.

Hospitals also vary significantly in the cases they consider appropriate for ECLS. What severity of illness is an indication for it? Presumably, hospitals that seek ECLS more proactively will have higher survival rates. Yet how many of those patients would survive anyhow? How many of those patients risk complications — bleeding, clotting or infections — because of ECLS? Could hospital resources be better used for other clinical cases, given that the median ECLS hospitalization costs more than $300,000 and involves near-constant attention from a multidisciplinary team?

The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, multidisciplinary at its core, has been both a pioneer and a tremendous force in pushing for standardization of ECLS care and education. But other professional societies have also developed separate sets of curricula, protocols for clinical care and performance measures related to their own discipline, leading to confusion and sometimes contradictory recommendations in the field. How should we teach ECLS to clinicians or judge their competence to manage these complex cases? Different professional societies set standards for their own groups, but they are not tied together.

In addition, there are no performance metrics for processes and outcomes associated with ECLS care that are agreed upon across societies and disciplines or by federal regulatory bodies.

All of these issues make it difficult to compare outcomes between centers, identify best practices or ensure clinicians are properly trained. Unless we as a unified ECLS community coordinate this work, the science of this rapidly evolving field will not keep pace with its growth, and patients may suffer.

Forging an International Collaborative

So, we had a thought: Why don’t we convene as many professional societies, researchers and organization who focus on ECLS to work collaboratively on a more coordinated, rigorous system? We sent invitations to organizations across the world, asking them to join us for a daylong retreat at the end of April. We weren't sure what kind of response to expect. We were grateful that 17 organizations hailing from seven countries found this issue important enough to make the trip.

When we gathered at the Armstrong Institute in Baltimore, there was almost a sense of urgency to tackle this issue so that if medical centers are using ECLS, they are doing it in a standardized, safe fashion and can assess their performance.

We broke into groups, with one focusing on evidence-based guidelines, one tackling education and curriculum development, and another working on creating valid performance metrics that are widely recognized — with the goal of coordinating these three spheres of activity. The group, now named the International Collaborative on Extracorporeal Life Support, plans to develop working groups for each of the three main topics of interest; meet a few times a year to continue working to mature the science and practice of ECLS; engage other stakeholders, including patients and health care regulatory agencies; and seek funding opportunities together.

We think this transdisciplinary approach, bringing together multiple stakeholders and disciplines so that we can work collaboratively instead of competitively, has promise for other areas of care. Too often, different professional societies and organizations work in silos. Likewise, those who work in evidence-based practice, training and measurement often work in their own worlds. This lack of coordination risks confusion, duplication and conflicting recommendations. We hope that this multisociety collaborative will inspire others to follow suit, challenge the sometimes-rigid traditional academic principal investigator-centered paradigm, and encourage open collaboration and flow of ideas to the benefit of our patients. We can accomplish great things when everyone truly collaborates without concern for who gets primary credit.

If you are involved in extracorporeal life support and would like to learn more about the new collaborative, please email [email protected].

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://www.binance.info/ar-BH/register-person?ref=V2H9AFPY

Bookmarking this for later. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

It was a pleasure reading this. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

Very practical and actionable tips. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

This brought real value to my day. Watch bbc news urdu today — Persian‑language breaking news, in‑depth reports, talk shows, and documentaries for Iran, Afghanistan, and the region. Reliable HD stream on any device. Including today's schedule.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Wow, awesome weblog structure! How lengthy have you ever been running a blog for?

you make blogging look easy. The overall glance of your websjte is magnificent, as

smmartly ass the content material! http://Boyarka-inform.com/