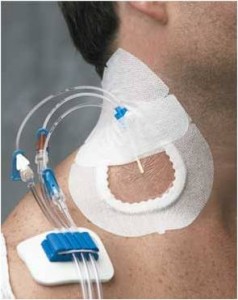

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare website added central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units to its list of publicly reported quality of care measures for individual hospitals.

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare website added central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units to its list of publicly reported quality of care measures for individual hospitals.

Why is this so important? There is universal support for the idea that the U.S. health care system should pay for value rather than volume, for the results we achieve rather than efforts we make. Health care needs outcome measures for the thousands of procedures and diagnoses that patients encounter. Yet we have few such measures and instead must gauge quality by looking to other public data, such as process of care measures (whether patients received therapies shown to improve outcomes) and results of patient surveys rating their hospital experiences.

Unfortunately, we lack a national approach to producing the large number of valid, reliable outcome measures that patients deserve. This is no easy task. Developing these measures is challenging and requires investments that haven’t yet been made.

The addition of bloodstream infections data is a huge step forward. These potentially lethal complications, measured using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s methods, are among the most accurately measured outcomes. In addition, the science of how to significantly reduce these infections is mature, and hundreds of hospitals of all types and sizes have nearly eliminated them. A program to reduce these infections that started at Johns Hopkins Hospital was spread throughout Michigan, and is now being implemented throughout the U.S., demonstrating substantial reductions.

Achieving these results isn’t easy. It requires hospital CEOs to commit to a goal of zero infections, as well as unit and infection prevention leaders to work together to meet that goal. ICU clinicians need to take ownership of this campaign, recognizing that bloodstream infection measures are a canary in the coal mine—an indicator of how well a quality improvement system is functioning.

Prior to adding bloodstream infections to Hospital Compare, the public had patchy information regarding hospitals’ infection rates. A handful of states made the data public and in those that did, we noticed a concerning trend. While most hospitals achieved reductions, a small number had high rates and failed to improve.

This is largely from lack of leadership focus, not because their patients are sicker and more susceptible to pathogens. In our national work focusing on bloodstream infections, we have seen that all types of hospitals and ICUs can dramatically reduce rates (though burn ICUs have higher rates than others).

Now that the public has data on bloodstream infection rates, let’s hope they use it, and let’s hope we finally create a mechanism to develop the many other measures that patients deserve. The key is to ensure that the measures are valid and that they tell the whole story. Our past research has revealed that “the more you look, the more you find” for certain complications, such as harmful blood clots. We don’t want hospitals to look worse than others in the public eye simply because they worked harder to identify when their patients were being harmed.

Public reporting has risks, and it can do more harm than good when the wrong measures are used. Though bloodstream infection rates are not a perfect measure, they perform well. Given that these infections kill approximately 30,000 people each year in the U.S. (slightly fewer than the number of people who die from breast or prostate cancer) and they are almost entirely preventable, they have not received the attention they deserve. The Hospital Compare website can help shine a light on those hospitals that need to redouble their efforts.

What should patients do with this data? First, if they think they may end up in an ICU, they should investigate the infection rates of their local hospitals. If a hospital has a high rate, they should discuss it with their physician and weigh the risks and benefits of seeking care elsewhere. Even if you are not seeking care and your local hospital has a high rate, write to the hospital’s CEO and board of trustees to ask what they are doing to reduce these infections, to honor their commitment to serve the community.

Bravo CMS, let’s hope this trend continues.

Note: Due to a technical glitch, bloodstream infection data for The Johns Hopkins Hospital was not immediately available on Hospital Compare, but it will be in the future. In the meantime, bloodstream infection data is available via the Maryland Health Care Commission at this link.

Read a related article on this new CMS measure.

This national report is a milestone that is built on the work of dedicated consumer and patient advocates around the country who have been the instigators of hospital infection laws in 30 states. As stated above, hospitals have been working to prevent these CLABSI infections for decades and we should be closer to eliminating them than we are. The work of Dr. Pronovost has helped to give them the tools, but this kind of public reporting should provide the impetus for those with a commitment to reach the goal of zero.

I have been unable to locate a Patient's Checklist for a stay in the hospital. Can you help?????

Thank You

Jerre--Sorry for the delayed response. If you're referring to the checklist mentioned recently in a USA Today article, it's in a post from December: https://armstronginstitute.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2011/12/20/a-safety-checklist-for-patients/. Thank you for your interest.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

I really like your blog.. very nice colors & theme.

Did you make this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for

you? Plz respond as I'm looking to create my own blog and would like to

know where u got this from. thanks a lot

I can’t wait to share this with others. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

Clear, concise, and effective. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.com/vi/register?ref=WTOZ531Y

Hi there colleagues, how is the whole thing,

and what you want to say about this piece of writing, in my view its truly remarkable in favor of me.

The company's shares, which rose over 4% in premarket trading earlier after

its pain drug and birth control patch succeeded in late-stage studies, were up 1.4%, after Viatris reported a goodwill impairment

charge of $2.9 billion.

'Our results suggest that vitamin D deficiency may contribute to the lack

of response to this first-line treatment of erectile dysfunction',

said Dr Miguel Olivencia, a researcher at Complutense University and co-author of the study.

yes. silly 😉

Trending Questions What is the taxonomic groupabove genus and below family?

When did he write Kensukes Kingdom? What is an example of a scientific statement?

What are some distinguishing characteristics of the phylum Arthropoda?

‘Shane was a really lovely man,' recalled the then 27-year-old Bovi.

‘He stripped off and laid on the bed for a back

rub with oils. He was very much at ease and comfortable… We were both

so shocked when we found out later that he had died.'

'His cognitive deficits significantly impair his ability to understand

the nature and consequences of the charges, consult with

counsel in a rational manner, and participate in his defense "with a reasonable degree of rational understanding,'' the.

The highly popular erectile dysfunction (ED) drug Viagra was

originally developed as a possible treatment for angina due to

its ability to boost blood circulation to the heart and stimulate the

release of nitric oxide (most natural male enhancement.

It is not possible to become uncircumcised, as circumcision is a surgical procedure that removes the

foreskin from the penis.

Trending Questions Is HTP addictive? What happens if

you combine Strattera and Adderall? Is white round pill gpi a325?

How many 25mg Xanax equals 2mg Xanax? Can you enlist

in the french foreign legion with a marijuana charge?

tank good ness aswome joke got from friends ttyl

It is generally not recommended to take ephedrine and Viagra together without consulting

a healthcare professional.

if you are taking 10mg of Lisinopril in the morning can you take

Viagra in the afternoon

Subscribed instantly after reading this. 👉 Watch Live Tv online in HD. Stream breaking news, sports, and top shows anytime, anywhere with fast and reliable live streaming.

When someone writes an article he/she retains the thought of a user in his/her brain that how

a user can be aware of it. Thus that's why this article is amazing.

Thanks!

my page; pink salt trick

What i don't realize is if truth be told how you're not really a lot more smartly-favored than you

might be now. You're very intelligent. You recognize thus

significantly on the subject of this matter, produced me personally imagine it from

so many varied angles. Its like men and women are not interested except it is something to accomplish with Girl

gaga! Your individual stuffs nice. Always take care of it up!

Aw, this was a very nice post. Taking a few minutes and

actual effort to create a very good article… but what can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and

don't manage to get anything done.

Review my web site pink salt trick

搜索露骨视频,通过探索网络上的可靠平台。研究 可靠的色情中心 以获得私密观看体验。

My homepage ... 阿尔拉·詹森 (http://www.covers.com)

It is not possible to become uncircumcised, as circumcision is a surgical procedure that removes the foreskin from

the penis.

成人视频 可在可靠平台上流媒体播放以确保隐私。发现 安全网站

以获得高质量观看体验。

Feel free to surf to my webpage; 顶级PURN网站

I felt like this was written just for me. Experience bbc persian television — Persian‑language breaking news. live bulletins and interviews. talk shows, feature stories, analysis programs. reliable HD stream on any device.

Viagra

Hi there, You've done a fantastic job. I'll certainly

digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I'm confident

they'll be benefited from this website.

Quality articles or reviews is the main to be a focus for the visitors to visit the website, that's what this web site is providing.

Hey there would you mind stating which blog platform you're using?

I'm looking to start my own blog soon but I'm

having a hard time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your layout seems different then most blogs and I'm

looking for something completely unique.

P.S Apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

I started fetching thc gummies a teeny-weeny while ago ethical to see what the hype was thither, and fashionable I indeed look forward to them preceding the time when bed. They don’t knock me escape or anything, but they make a show it so much easier to chill and disappointing collapse asleep naturally. I’ve been waking up feeling feature more rested and not sluggish at all. Disinterestedly, friendly of disposition I’d tried them sooner.