The Value of Safer Care

What is it worth to be treated in a hospital with a stellar patient safety record rather than one with lower performance? For a large… Read More »The Value of Safer Care

What is it worth to be treated in a hospital with a stellar patient safety record rather than one with lower performance? For a large… Read More »The Value of Safer Care

Across health care, organizations constantly struggle with the challenge of achieving patient safety and quality successes on a large scale—across a hospital or network of hospitals. Too often, they are doomed at the start, because staff don’t even know what the goals are. In other cases, staff have limited capacity to carry out improvement work and few resources available to help them. Subpar performance is allowed to continue without any accountability, assuming that they know how well they are performing in the first place.

At Johns Hopkins Medicine, we are proud of an effort that has not only improved patient care, but has also provided a blueprint for how we can tackle any number of challenges in improving patient care—such as eliminating infections or enhancing the patient experience—across complex health care organizations.

Last week three hospitals within Johns Hopkins Medicine were recognized by the Joint Commission as “Top Performers” in patient safety and quality, for consistently following evidence-based practices at a very high level. Those hospitals—The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C. and All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla.—benefitted from an organization-wide approach that enlisted local teams in problem solving, directed core resources to support those teams, and made units, departments and hospitals accountable for their performance.

Last week the Armstrong Institute, along with our partners at the World Health Organization, had the privilege of hosting more than 200 clinicians, patient advocates, health care leaders and policy makers for our inaugural Forum on Emerging Topics in Patient Safety in Baltimore.

The event featured presentations by international experts in a dozen different industries, including aviation safety expert Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, a former space shuttle commander and the chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Other speakers shared their expertise in education, sociology, engineering, nuclear power and hospitality to see what untapped lessons such fields may hold for health care.

Their collective expertise was breathtaking. What was even more impressive was the obvious enthusiasm and spirit of collaboration embodied by a group joined by a common and noble purpose: to overcome the complex challenges that allow preventable patient harm to persist.

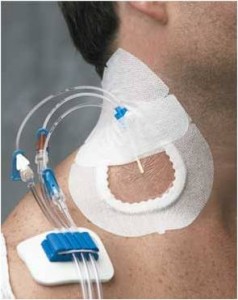

At Johns Hopkins, we’ve already seen what’s possible when health care adopts best practices from other industries. Our work to reduce central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSI) presents a powerful example. By coupling an aviation-style checklist of best practices to prevent these infections with a culture change program that empowers front-line caregivers to take ownership for patient safety, the program, detailed recently on Health Affairs Blog, has reduced CLABSI in hospital intensive care units across the country by more than 40 percent. Similar results have been replicated in Spain, England, Peru and Pakistan.

That effort succeeded because we challenged and changed paradigms traditionally accepted by the health care community. We helped convince teams that patient harm is preventable, not inevitable. That health care is delivered by an expert team, not a team of experts. And, most importantly, that by working together, health care stakeholders can overcome barriers to improvement.

But if there are to be more national success stories in quality improvement, I believe the health care community will need to examine a few of its other beliefs.

Where health care has fallen short in significantly improving quality, our peers in other high-risk industries have thrived. Perhaps we can adapt and learn from their lessons.

Where health care has fallen short in significantly improving quality, our peers in other high-risk industries have thrived. Perhaps we can adapt and learn from their lessons.

For example, health care can learn much from the nuclear power industry, which has markedly improved its safety track record over the last two decades since peer-review programs were implemented. Created in the wake of two nuclear crises, these programs may provide a powerful model for health care organizations.

Following the famous Three Mile Island accident, a partial nuclear meltdown near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in spring 1979, the Institute of Nuclear Power Operators (INPO) was formed by the CEOs of the nuclear companies. That organization established a peer-to-peer assessment program to share best practices, safety hazards, problems and actions that improved safety and operational performance. In the U.S., no serious nuclear accidents have occurred since then.

At Johns Hopkins Medicine, we recently held our fourth annual Patient Safety Summit, a daylong gathering in which faculty and staff from across our health system share their work to reduce patient harm and foster a culture of safety. The event has quickly become a tradition, with more than 425 participants flocking annually to our East Baltimore campus to sample from a wide range of presentations and network with colleagues.

As I attended the summit, I was struck by how much our own internal patient safety movement has matured, and it gave me hope for the future of the larger patient safety effort.

When we held the first summit in 2010, the enthusiasm for patient safety was high, but the science was not always at the same level. While many of the poster presenters were excellent clinicians and staff who offered thoughtful suggestions on how to improve patient safety, their work was frequently weak on data, used simple methods and lacked theory.

This year’s summit featured 75 posters and 43 presentations, but the scope and quality of the science was breathtaking. Watch this video to hear highlights from this year’s poster presenters.

Read More »Patient Safety Summit: Four Years of Advancing the Science

If you have ever tried to choose a physician or hospital based on publicly available performance measures, you may have felt overwhelmed and confused by what you found online. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Joint Commission, the Leapfrog Group, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, as well as most states and for-profit companies such as Healthgrades and U.S. News and World Report, all offer various measures, ratings, rankings and report cards. Hospitals are even generating their own measures and posting their performance on their websites, typically without validation of their methodology or data.

If you have ever tried to choose a physician or hospital based on publicly available performance measures, you may have felt overwhelmed and confused by what you found online. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Joint Commission, the Leapfrog Group, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, as well as most states and for-profit companies such as Healthgrades and U.S. News and World Report, all offer various measures, ratings, rankings and report cards. Hospitals are even generating their own measures and posting their performance on their websites, typically without validation of their methodology or data.

The value and validity of these measures varies greatly, though their accuracy is rarely publically reported. Even when methodologies are transparent, clinicians, insurers, government agencies and others frequently disagree on whether a measure accurately indicates the quality of care. Some companies’ methods are proprietary and, unlike many other publicly available measures, have not been reviewed by the National Quality Forum, a public-private organization that endorses quality measures.

Depending where you look, you often get a different story about the quality of care at a given institution. For example, none of the 17 hospitals listed in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Hospitals Honor Roll” were identified by the Joint Commission as top performers in its 2010 list of institutions that received a composite score of at least 95 percent on key process measures. In a recent policy paper, Robert Berenson, a fellow at the Urban Institute, Harlan Krumholz, of the Yale-New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, and I called for dramatic change in measurement. (Thanks to The Health Care Blog for highlighting this analysis recently.)

I recently cared for Ms. K, an elderly black woman who had been sitting in the intensive care unit for more than a month. She was, frail, weak and intermittently delirious, with a hopeful smile. She had a big problem: She had undergone an esophagectomy at an outside hospital and suffered a horrible complication, leading her to be transferred to The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ms. K had a large hole in her posterior trachea, far too large to directly fix, extending from her vocal cords to where her trachea splits into right and left bronchus. She had a trachea tube so she can breathe, and her esophagus was tied off high in her throat so oral secretions containing bacteria did not fall through the hole and infect her heart and lungs. It is unclear if she will survive, and the costs of her medical care will be in the millions.

I recently cared for Ms. K, an elderly black woman who had been sitting in the intensive care unit for more than a month. She was, frail, weak and intermittently delirious, with a hopeful smile. She had a big problem: She had undergone an esophagectomy at an outside hospital and suffered a horrible complication, leading her to be transferred to The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ms. K had a large hole in her posterior trachea, far too large to directly fix, extending from her vocal cords to where her trachea splits into right and left bronchus. She had a trachea tube so she can breathe, and her esophagus was tied off high in her throat so oral secretions containing bacteria did not fall through the hole and infect her heart and lungs. It is unclear if she will survive, and the costs of her medical care will be in the millions.

Ms K’s complication is tragic—and largely preventable. For the type of surgery she had, there is a strong volume-outcome relationship: Those hospitals that perform more than 12 cases a year have significantly lower mortality. This finding, based on significant research, is made transparent by the Leapfrog Group and several insurers, who use a performance measure that combines the number of cases performed with the mortality rate. Hopkins Hospital performs more than 100 of these procedures a year, and across town, the University of Maryland tallies about 60. The hospital where Ms. K had her surgery did one last year. One. While the exact relationship between volume and outcome is imprecise, it is no wonder she had a complication.

Ms. K is not alone. Of the 45 Maryland hospitals that perform this surgery, 56 percent had fewer than 12 cases last year and 38 percent had fewer than six.

One day, after the ICU team—nurses, medical students, residents, critical care fellows and the attending—made rounds on Ms. K, we stepped outside of her room. We talked about what we could do to help get her well and to a lower level of care. But we also discussed the evidence for the volume-outcome relationship, highlighting that the hospital that performed Ms. K’s operation performed one in the previous year. Upon hearing this, the medical students cringed, quizzically looking at each other as if observing a violent act. The residents and fellows, the more experienced clinicians, stood expressionless; they commonly see this type of tragedy.Read More »See one, do one, harm one?

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare website added central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units to its list of publicly reported quality of care measures for individual hospitals.

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare website added central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units to its list of publicly reported quality of care measures for individual hospitals.

Why is this so important? There is universal support for the idea that the U.S. health care system should pay for value rather than volume, for the results we achieve rather than efforts we make. Health care needs outcome measures for the thousands of procedures and diagnoses that patients encounter. Yet we have few such measures and instead must gauge quality by looking to other public data, such as process of care measures (whether patients received therapies shown to improve outcomes) and results of patient surveys rating their hospital experiences.

Unfortunately, we lack a national approach to producing the large number of valid, reliable outcome measures that patients deserve. This is no easy task. Developing these measures is challenging and requires investments that haven’t yet been made.

Read More »To gauge hospital quality, patients deserve more outcome measures

I recently spoke to an executive in the energy industry who had a joint replacement at a hospital in New York. His wound developed an infection, which required four additional hospital admissions and several operations. He asked me about hand hygiene in hospitals. Proudly, I told him that, at Johns Hopkins Hospital, we are at 80 percent compliance with hand hygiene, up from 30 percent not that long ago. I focused on the improvement. He focused on the failures. "So," he said pointedly, "one in five times you do not comply with basic hand washing rules, potentially causing infections—or even death." He asked what we are doing about it.

I told him how we try to learn from the high performers and to improve the poor performers, how we train staff on the importance of hand hygiene, how we report compliance rates to unit teams, how we put pictures of patients with the words “please wash” outside their rooms.

The executive said, "All that is great, but where is the accountability?" In any other industry, there is accountability to ensure staff comply with safety standards, standards that are often much less consequential than hand washing. Other industries help staff improve compliance; they also hold local managers accountable for poor performance. To get results, you must both support staff and hold them responsible.

Read More »Health care needs greater accountability, not excuses