Company churns out burritos, French toast — and inspiration for health care

This year I am participating in an executive fellowship that is designed to expose leaders in various industries to the Baldrige Framework, a model for organizational excellence. As part of the program, the fellows visit companies that received the coveted Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award, administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Recently, we toured Cargill, a large, Minnesota-based company that has about 75 business units, and spent time with two of them: Cargill Kitchen Solutions, which largely makes egg products for McDonald’s, schools and many other customers; and Cargill Corn Milling, a maker of corn syrup, animal food and ethanol.

We not only talked to leaders and reviewed their strategic plans, but visited the plant. We spoke to employees on the floor, as food was prepared on a massive scale: eggs being cooked by the thousands, breakfast burritos being assembled and placed on conveyor belts, French toast cooked, stacked and placed into boxes.

As we talked to leaders, toured the plant and reviewed their strategic plans, I was struck by three things.

First, everything and everybody was focused on the customer. The customer was at the center of every discussion, every decision and every strategy. From the CEO to the managers to people on the shop floor, they talked about meeting customers’ needs. Usually it was the first thing out of their mouths, and they used the impact on customers as a scale for weighing every decision. Indeed, many staff, from senior leaders to line operators making an hourly wage, said, We know who pays our paycheck; it’s the customer. If we want a paycheck, we better meet their needs.Read More »Company churns out burritos, French toast — and inspiration for health care

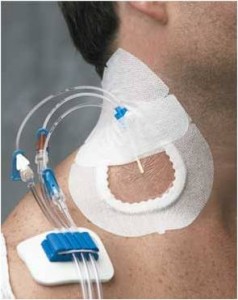

I recently cared for Ms. K, an elderly black woman who had been sitting in the intensive care unit for more than a month. She was, frail, weak and intermittently delirious, with a hopeful smile. She had a big problem: She had undergone an esophagectomy at an outside hospital and suffered a horrible complication, leading her to be transferred to The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ms. K had a large hole in her posterior trachea, far too large to directly fix, extending from her vocal cords to where her trachea splits into right and left bronchus. She had a trachea tube so she can breathe, and her esophagus was tied off high in her throat so oral secretions containing bacteria did not fall through the hole and infect her heart and lungs. It is unclear if she will survive, and the costs of her medical care will be in the millions.

I recently cared for Ms. K, an elderly black woman who had been sitting in the intensive care unit for more than a month. She was, frail, weak and intermittently delirious, with a hopeful smile. She had a big problem: She had undergone an esophagectomy at an outside hospital and suffered a horrible complication, leading her to be transferred to The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ms. K had a large hole in her posterior trachea, far too large to directly fix, extending from her vocal cords to where her trachea splits into right and left bronchus. She had a trachea tube so she can breathe, and her esophagus was tied off high in her throat so oral secretions containing bacteria did not fall through the hole and infect her heart and lungs. It is unclear if she will survive, and the costs of her medical care will be in the millions. The video of

The video of  In the world of patient safety, we’re constantly reinforcing the importance of teamwork and communication, both among clinicians and with patients. That’s because we know that patient harm so often occurs when vital information about a patient’s care is omitted, miscommunicated or ignored.

In the world of patient safety, we’re constantly reinforcing the importance of teamwork and communication, both among clinicians and with patients. That’s because we know that patient harm so often occurs when vital information about a patient’s care is omitted, miscommunicated or ignored. Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’  I was reminded again recently of how important it is to sometimes just sit back and listen to what our patients have to say. Every month, as part of our hospital-wide patient safety efforts, I meet with staff and interview patients, seeking to learn how we can improve the care we provide to them.

I was reminded again recently of how important it is to sometimes just sit back and listen to what our patients have to say. Every month, as part of our hospital-wide patient safety efforts, I meet with staff and interview patients, seeking to learn how we can improve the care we provide to them. Far too many patients are harmed rather than helped from their interactions with the health care system. While reducing this harm has proven to be devilishly difficult, we have found that checklists help. Checklists help to reduce ambiguity about what to do, to prioritize what is most important, and to clarify the behaviors that are most helpful.

Far too many patients are harmed rather than helped from their interactions with the health care system. While reducing this harm has proven to be devilishly difficult, we have found that checklists help. Checklists help to reduce ambiguity about what to do, to prioritize what is most important, and to clarify the behaviors that are most helpful.