Re-engineering health care for safety and cost savings

Despite spending $800 billion on technology last year, health care productivity is flat and preventable patient harm remains the third leading cause of death in the U.S.

One reason is that health care is grossly under-engineered: medical devices don't talk to each other, treatments are not specified and ensured, and outcomes are largely assumed rather than measured.

Other industries rely much less on heroism by individuals and more on designing safe systems and using technology to support work. Today a pilot’s cockpit is much simpler than 30 years ago; it is far more error-proof, and built-in defenses enhance safety. By comparison, hospital intensive care units, which contain anywhere from 50 to 100 pieces of separate electronic equipment, appear unchanged.

Changing this will require unprecedented collaboration between health care’s many stakeholders. That’s one reason why this fall the Armstrong Institute and the World Health Organization convened health care leaders, consumers, providers, regulators and private-industry partners to discuss such topics as how to design safer systems at the Forum on Emerging Topics in Patient Safety held in Baltimore.

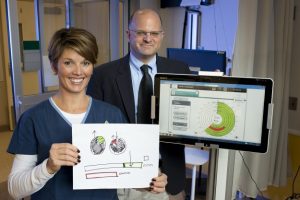

One effort to design safer systems at Johns Hopkins is Project Emerge. Supported by a $9.4 million grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Emerge is tapping into the wisdom of a diverse team of engineers, nurses, doctors, bioethicists, and patients and family members — 18 disciplines in all from across Johns Hopkins University— to design safer care in ICUs.

Read More »Re-engineering health care for safety and cost savings