Dreaming the dream

The video of Susan Boyle’s debut on Britain’s Got Talent is well worth watching. She walked on stage, wearing a frumpy dress, overweight and awkward. Members of the audience snickered and rolled their eyes as this 47-year-old told the judges that she wanted to be a singing star. I suspect she had her own doubts. Yet she had the courage to try. She believed in herself and stunned the audience with her voice.

The video of Susan Boyle’s debut on Britain’s Got Talent is well worth watching. She walked on stage, wearing a frumpy dress, overweight and awkward. Members of the audience snickered and rolled their eyes as this 47-year-old told the judges that she wanted to be a singing star. I suspect she had her own doubts. Yet she had the courage to try. She believed in herself and stunned the audience with her voice.

Susan’s story is typical of so many personal journeys. We face skepticism from others, and we are filled with self-doubt. Sometimes we listen to those little voices whispering: You cannot do this. Yet when we overcome the doubts, we are often successful. If we give into those voices, we will surely fail.

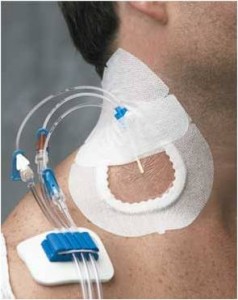

This same self-doubt exists in patient safety. I know because I had plenty of uncertainty about my ability to reduce patient harm. More than a decade ago, we decided to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections on one intensive care unit. We doubted it was possible and whether we could have a role in reducing harm. Most of the physicians thought it couldn’t be done. Sick people get infected, they said. These infections just happen. In our own way, we felt frumpy and awkward.

Initially, we did not debate whether we could stop these infections. We focused on consistently following those practices shown by evidence to reduce them. We had been complying with those practices just 30 percent of the time. Our clinicians agreed that we would follow a checklist to help ensure 100 percent compliance and then see what happened to our infections. As compliance rose, the rates went to nearly zero, and the doubts disappeared.

In the world of patient safety, we’re constantly reinforcing the importance of teamwork and communication, both among clinicians and with patients. That’s because we know that patient harm so often occurs when vital information about a patient’s care is omitted, miscommunicated or ignored.

In the world of patient safety, we’re constantly reinforcing the importance of teamwork and communication, both among clinicians and with patients. That’s because we know that patient harm so often occurs when vital information about a patient’s care is omitted, miscommunicated or ignored. Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’

Patients, providers and the public have much to celebrate. This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’  I was reminded again recently of how important it is to sometimes just sit back and listen to what our patients have to say. Every month, as part of our hospital-wide patient safety efforts, I meet with staff and interview patients, seeking to learn how we can improve the care we provide to them.

I was reminded again recently of how important it is to sometimes just sit back and listen to what our patients have to say. Every month, as part of our hospital-wide patient safety efforts, I meet with staff and interview patients, seeking to learn how we can improve the care we provide to them. Far too many patients are harmed rather than helped from their interactions with the health care system. While reducing this harm has proven to be devilishly difficult, we have found that checklists help. Checklists help to reduce ambiguity about what to do, to prioritize what is most important, and to clarify the behaviors that are most helpful.

Far too many patients are harmed rather than helped from their interactions with the health care system. While reducing this harm has proven to be devilishly difficult, we have found that checklists help. Checklists help to reduce ambiguity about what to do, to prioritize what is most important, and to clarify the behaviors that are most helpful.

Last year, Sarah Andryauskas, then a new nurse in our emergency department, was caring for a patient with diabetes who had trouble maintaining healthy blood glucose levels. His disease had contributed to several hospital visits over the preceding months and years.

Last year, Sarah Andryauskas, then a new nurse in our emergency department, was caring for a patient with diabetes who had trouble maintaining healthy blood glucose levels. His disease had contributed to several hospital visits over the preceding months and years.