Changing The Conversation About Patient-Centered Care

Earlier this year, our hospital staff was weighing a new 24/7 family presence policy to allow immediate family members to stay with patients 24 hours a day. We knew this was a step in the direction of delivering patient- and family-centered care.

We presented the proposal at a meeting of our Patient and Family Advisory Council. One of the members of the council told a story that drove home the importance of this decision. When her son was battling a fatal illness in the hospital, she had to leave him when visiting hours ended. She couldn’t stand the thought of being far away, she told the group, so instead of going home she slept in her car in the hospital’s parking garage.

It’s hard to gauge exactly how her story ultimately affected The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s new 24/7 family presence policy. But one thing is clear: Involving patients and family members in decision-making fundamentally changes the conversation for the better, whether the issue involves an individual treatment decision or a hospital-wide policy. Charlene Rothkopf, a former patient who sits on two of our health system’s safety and quality boards, puts it so eloquently. “Many times our health care professionals get so caught up in the day-to-day press of business, that they may lose sight of the real meaning of what they’re there for,” she says. “Patients help bring that to light.” Patients appreciate the importance of simple things, such as discussing their concerns about an upcoming surgery or providing a compassionate touch, she says.

Sadly, the status quo in health care does not always engage patients and their loved ones, and we are all less healthy for it. We don’t always ask patients what their goals are for their care. We sometimes forget to introduce ourselves by name when we walk into a room. We deliver aggressive and expensive treatments to prolong life, without always having conversations with patients to determine whether they want these well-intentioned steps. We confuse patients with a stream of physicians and nurses that leaves them wondering who, if anyone, is overseeing and coordinating their overall care. We send patients out of the hospital without a clear understanding of how to provide self-care or without hard-wiring the connection to their outpatient physicians.Read More »Changing The Conversation About Patient-Centered Care

This week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued two reports that are simultaneously scary and encouraging.

This week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued two reports that are simultaneously scary and encouraging. The doughnut shop I pass on my drive to the hospital isn't the kind of place where you might expect to see outpourings of random kindness. It sits in the shadow of a raised highway, a few doors down from a bail bond business and a block away from a prison complex that resembles a medieval castle. One Sunday before Valentine’s Day, the line to get served there was long, checkered with homeless people—some of whom sleep under the highway to stay dry and protected from the wind—and more well-off people getting breakfast or bringing bagels or doughnuts to work or church.

The doughnut shop I pass on my drive to the hospital isn't the kind of place where you might expect to see outpourings of random kindness. It sits in the shadow of a raised highway, a few doors down from a bail bond business and a block away from a prison complex that resembles a medieval castle. One Sunday before Valentine’s Day, the line to get served there was long, checkered with homeless people—some of whom sleep under the highway to stay dry and protected from the wind—and more well-off people getting breakfast or bringing bagels or doughnuts to work or church. One of the most exciting things about working in patient safety and health care quality is that it’s not solely about advancing science or applying performance improvement methods. It is also about the excitement of being part of a social movement that is changing the culture of medicine—putting patients at the center of everything, sharing errors in the hopes of preventing future ones, and confronting hierarchies that stifle communication and innovation.

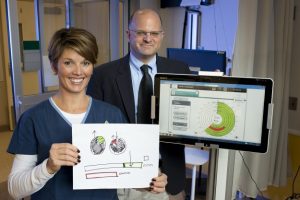

One of the most exciting things about working in patient safety and health care quality is that it’s not solely about advancing science or applying performance improvement methods. It is also about the excitement of being part of a social movement that is changing the culture of medicine—putting patients at the center of everything, sharing errors in the hopes of preventing future ones, and confronting hierarchies that stifle communication and innovation. Frontline caregivers across the United States—and in many other countries, no doubt—are bombarded by multiple quality improvement (QI) projects. A clinical unit might simultaneously be engaged in efforts to reduce readmissions, eliminate hospital-acquired infections and other complications, increase hand-hygiene compliance, improve performance on core measures, and enhance the patient experience. The demands brought by participating in all of these efforts risk overwhelming health care professionals, who are already stretched thin in an environment of reduced reimbursements and health care reform.

Frontline caregivers across the United States—and in many other countries, no doubt—are bombarded by multiple quality improvement (QI) projects. A clinical unit might simultaneously be engaged in efforts to reduce readmissions, eliminate hospital-acquired infections and other complications, increase hand-hygiene compliance, improve performance on core measures, and enhance the patient experience. The demands brought by participating in all of these efforts risk overwhelming health care professionals, who are already stretched thin in an environment of reduced reimbursements and health care reform.